References

Arnold MJ, Gaillardetz A, Ohiokpehai J (2023) Benign prostatic hyperplasia: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 107(6):613-622

Bibok A, Kis B, Parikh N (2024) Prostate artery embolization with 4D-CT. Semin Intervent Radiol. 41(3):302-308. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1788622

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023a) Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP). Leaflet No: E23/095. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/HoLEP.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023b) Rezūm (steam ablation) treatment for benign prostate enlargement. Leaflet No: 23/186. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Rezum.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023c) Green light laser prostatectomy. Leaflet No: E23/190. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Greenlight.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023d) Prostatic urethral lift (UroLift) implant. Leaflet No: E23/179. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Urolift.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023e) Incision of the bladder neck. Leaflet No: E23/100. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/patients/leaflets/Bladder%20neck%20incision.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023f) Transurethral resection of the prostate for benign disease. Leaflet No: E23/109. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/TURP%20for%20benign.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2024) Endoscopic (telescopic) treatment of a urethral stricture. Leaflet No: A24/152. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Endoscopic%20stricture%20treatment.pdf (accessed 10 November 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2025a) Prostate symptoms (bladder outlet obstruction). https://www.baus.org.uk/patients/conditions/9/prostate_symptoms_bladder_outlet_obstruction/ (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2025b) Open (Millin’s) prostatectomy for benign obstruction. Leaflet No: 025/096. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Millin.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

Cho JM, Moon KT, Yoo TK (2020) Robotic simple prostatectomy: why and how? Int Neurourol J. 24(1):12-20. https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2040018.009

Christidis D, McGrath S, Perera M, Manning T, Bolton D, Lawrentschuk N (2017) Minimally invasive surgical therapies for benign prostatic hypertrophy: The rise in minimally invasive surgical therapies. Prostate Int. 5(2):41-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prnil.2017.01.007

Das AK, Han TM, Uhr A, Roehrborn CG (2020) Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an update on minimally invasive therapy including Aquablation. Can J Urol. 27(S3):2-10

Elterman D, Shepherd S, Saadat SH et al (2021) Prostatic urethral lift (UroLift) versus convective water vapor ablation (Rezum) for minimally invasive treatment of BPH: a comparison of improvements and durability in 3-year clinical outcomes. Can J Urol. 28(5):10824-10833

Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P et al (2018) Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline. J Urol. 200(3):612-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.048

Franco JV, Jung JH, Imamura M et al (2021) Minimally invasive treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7(7):CD013656. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013656.pub2

Guo Y (2015) AB001. Transurethral balloon dilatation of prostate in treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Transl Androl Urol. 4(S1):AB001. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.s001

Johnson B, Sorokin I, Singla N, Roehrborn C, Gahan JC (2018) Determining the learning curve for robot-assisted simple prostatectomy in surgeons familiar with robotic surgery. J Endourol. 32(9):865-870. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0377

Leslie SW, Chargui S, Stormont G (2023) Transurethral resection of the prostate. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560884/ (accessed 31 October 2025)

Liu HH, Tsai TH, Lee SS, Kuo YH, Hsieh T (2016) Maximum urine flow rate of less than 15ml/sec increasing risk of urine retention and prostate surgery among patients with alpha-1 blockers: a 10-year follow up study. PLoS One. 11(8):e0160689. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160689

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: assessment and management. Clinical guideline CG97. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg97 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care. Clinical guideline CG139. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Prostate artery embolisation for lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia. Interventional procedures guidance IPG611. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg611 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) Rezum for treating lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG49. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg49 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) UroLift for treating lower urinary tract symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG58. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg58 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2022) GreenLight XPS for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG74. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg74 (accessed 31 October 2025)

Nguyen DD, Li T, Ferreira R et al (2024) Ablative minimally invasive surgical therapies for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A review of Aquablation, Rezum, and transperineal laser prostate ablation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 27(1):22-28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-023-00669-z

Park S, Ryu JM, Lee M (2020) Quality of life in older adults with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Healthcare (Basel). 8(2):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020158

Pham H, Sharma P (2018) Emerging, newly-approved treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Can J Urol. 25(2):9228-9237

Sotelo R, Clavijo R, Carmona O, Garcia A, Banda E, Miranda M, Fagin R (2008) Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 179(2):513-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.065

Speakman M, Kirby R, Doyle S, Ioannou C (2015) Burden of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - focus on the UK. BJU Int. 115(4):508-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12745

Srinivasan A, Wang R (2020) An update on minimally invasive surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia: techniques, risks, and efficacy. World J Mens Health. 38(4):402-411. https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.190076

Wasserman NF, Niendorf E, Spilseth B (2020) Measurement of prostate volume with MRI (a guide for the perplexed): biproximate method with analysis of precision and accuracy. Sci Rep. 10(1):575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57046-x

Xia Z, Li J, Yang X et al (2021) Robotic-assisted vs. open simple prostatectomy for large prostates: a meta-analysis. Front Surg. 8:695318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.695318

Ye Z, Wang J, Xiao Y, Luo J, Xu L, Chen Z (2024) Global burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in males aged 60-90 years from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Urol. 24(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-024-01582-w

Young MJ, Elmussareh M, Morrison T, Wilson R (2018) The changing practice of transurethral resection of the prostate. Ann Royal Coll Surg Eng. 100(4):326-329. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2018.0054

Bibok A, Kis B, Parikh N (2024) Prostate artery embolization with 4D-CT. Semin Intervent Radiol. 41(3):302-308. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1788622

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023a) Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP). Leaflet No: E23/095. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/HoLEP.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023b) Rezūm (steam ablation) treatment for benign prostate enlargement. Leaflet No: 23/186. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Rezum.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023c) Green light laser prostatectomy. Leaflet No: E23/190. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Greenlight.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023d) Prostatic urethral lift (UroLift) implant. Leaflet No: E23/179. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Urolift.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023e) Incision of the bladder neck. Leaflet No: E23/100. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/patients/leaflets/Bladder%20neck%20incision.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2023f) Transurethral resection of the prostate for benign disease. Leaflet No: E23/109. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/TURP%20for%20benign.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2024) Endoscopic (telescopic) treatment of a urethral stricture. Leaflet No: A24/152. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Endoscopic%20stricture%20treatment.pdf (accessed 10 November 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2025a) Prostate symptoms (bladder outlet obstruction). https://www.baus.org.uk/patients/conditions/9/prostate_symptoms_bladder_outlet_obstruction/ (accessed 31 October 2025)

British Association of Urological Surgeons (2025b) Open (Millin’s) prostatectomy for benign obstruction. Leaflet No: 025/096. https://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Millin.pdf (accessed 31 October 2025)

Cho JM, Moon KT, Yoo TK (2020) Robotic simple prostatectomy: why and how? Int Neurourol J. 24(1):12-20. https://doi.org/10.5213/inj.2040018.009

Christidis D, McGrath S, Perera M, Manning T, Bolton D, Lawrentschuk N (2017) Minimally invasive surgical therapies for benign prostatic hypertrophy: The rise in minimally invasive surgical therapies. Prostate Int. 5(2):41-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prnil.2017.01.007

Das AK, Han TM, Uhr A, Roehrborn CG (2020) Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an update on minimally invasive therapy including Aquablation. Can J Urol. 27(S3):2-10

Elterman D, Shepherd S, Saadat SH et al (2021) Prostatic urethral lift (UroLift) versus convective water vapor ablation (Rezum) for minimally invasive treatment of BPH: a comparison of improvements and durability in 3-year clinical outcomes. Can J Urol. 28(5):10824-10833

Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P et al (2018) Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline. J Urol. 200(3):612-619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.048

Franco JV, Jung JH, Imamura M et al (2021) Minimally invasive treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7(7):CD013656. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013656.pub2

Guo Y (2015) AB001. Transurethral balloon dilatation of prostate in treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Transl Androl Urol. 4(S1):AB001. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.s001

Johnson B, Sorokin I, Singla N, Roehrborn C, Gahan JC (2018) Determining the learning curve for robot-assisted simple prostatectomy in surgeons familiar with robotic surgery. J Endourol. 32(9):865-870. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0377

Leslie SW, Chargui S, Stormont G (2023) Transurethral resection of the prostate. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560884/ (accessed 31 October 2025)

Liu HH, Tsai TH, Lee SS, Kuo YH, Hsieh T (2016) Maximum urine flow rate of less than 15ml/sec increasing risk of urine retention and prostate surgery among patients with alpha-1 blockers: a 10-year follow up study. PLoS One. 11(8):e0160689. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160689

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) Lower urinary tract symptoms in men: assessment and management. Clinical guideline CG97. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg97 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care. Clinical guideline CG139. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Prostate artery embolisation for lower urinary tract symptoms caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia. Interventional procedures guidance IPG611. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg611 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) Rezum for treating lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG49. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg49 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) UroLift for treating lower urinary tract symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG58. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg58 (accessed 31 October 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2022) GreenLight XPS for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia. Medical technologies guidance MTG74. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg74 (accessed 31 October 2025)

Nguyen DD, Li T, Ferreira R et al (2024) Ablative minimally invasive surgical therapies for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A review of Aquablation, Rezum, and transperineal laser prostate ablation. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 27(1):22-28. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-023-00669-z

Park S, Ryu JM, Lee M (2020) Quality of life in older adults with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Healthcare (Basel). 8(2):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020158

Pham H, Sharma P (2018) Emerging, newly-approved treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Can J Urol. 25(2):9228-9237

Sotelo R, Clavijo R, Carmona O, Garcia A, Banda E, Miranda M, Fagin R (2008) Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 179(2):513-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.065

Speakman M, Kirby R, Doyle S, Ioannou C (2015) Burden of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - focus on the UK. BJU Int. 115(4):508-19. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.12745

Srinivasan A, Wang R (2020) An update on minimally invasive surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia: techniques, risks, and efficacy. World J Mens Health. 38(4):402-411. https://doi.org/10.5534/wjmh.190076

Wasserman NF, Niendorf E, Spilseth B (2020) Measurement of prostate volume with MRI (a guide for the perplexed): biproximate method with analysis of precision and accuracy. Sci Rep. 10(1):575. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-57046-x

Xia Z, Li J, Yang X et al (2021) Robotic-assisted vs. open simple prostatectomy for large prostates: a meta-analysis. Front Surg. 8:695318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.695318

Ye Z, Wang J, Xiao Y, Luo J, Xu L, Chen Z (2024) Global burden of benign prostatic hyperplasia in males aged 60-90 years from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Urol. 24(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-024-01582-w

Young MJ, Elmussareh M, Morrison T, Wilson R (2018) The changing practice of transurethral resection of the prostate. Ann Royal Coll Surg Eng. 100(4):326-329. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2018.0054

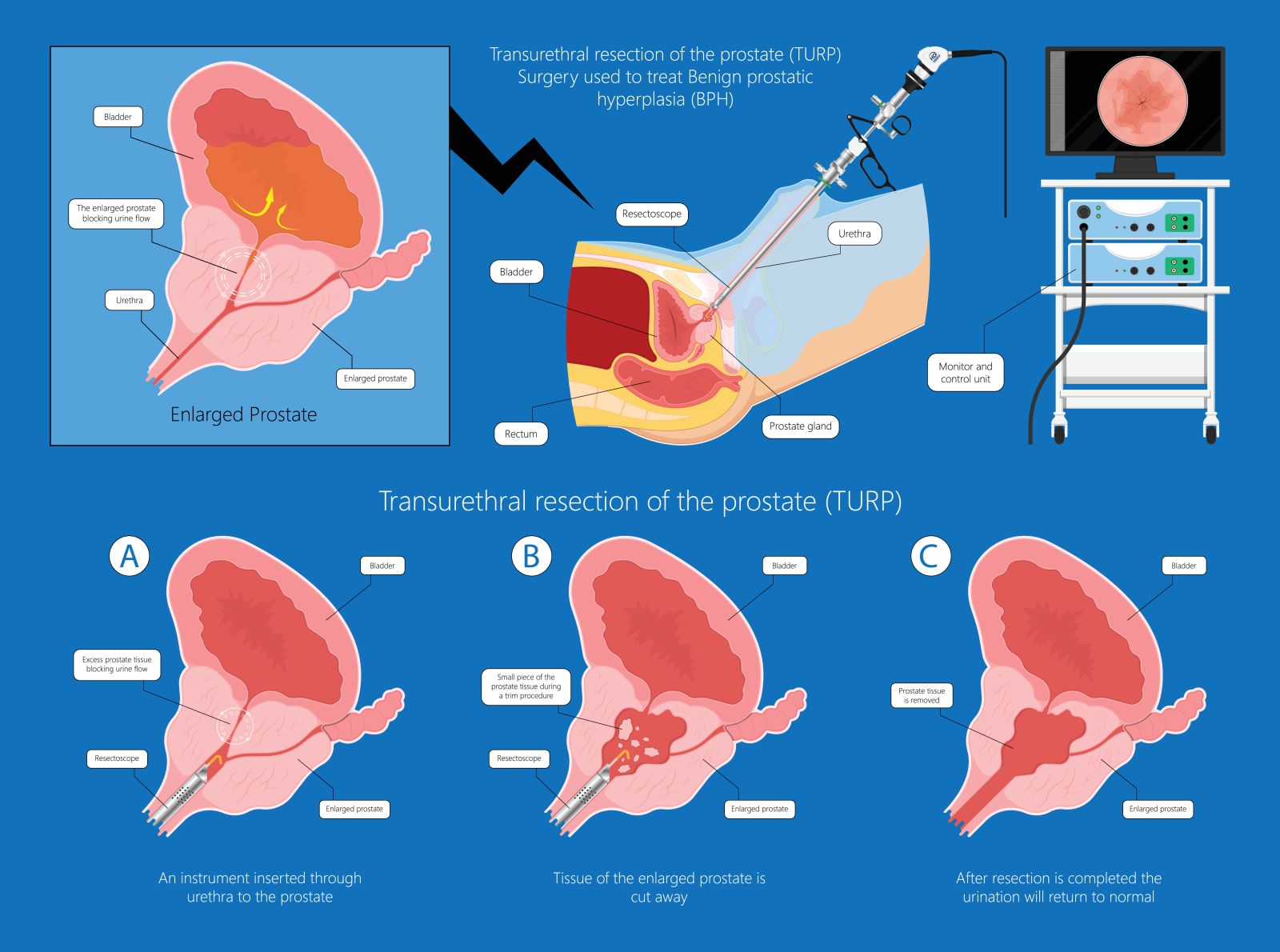

Figure 1. Treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia

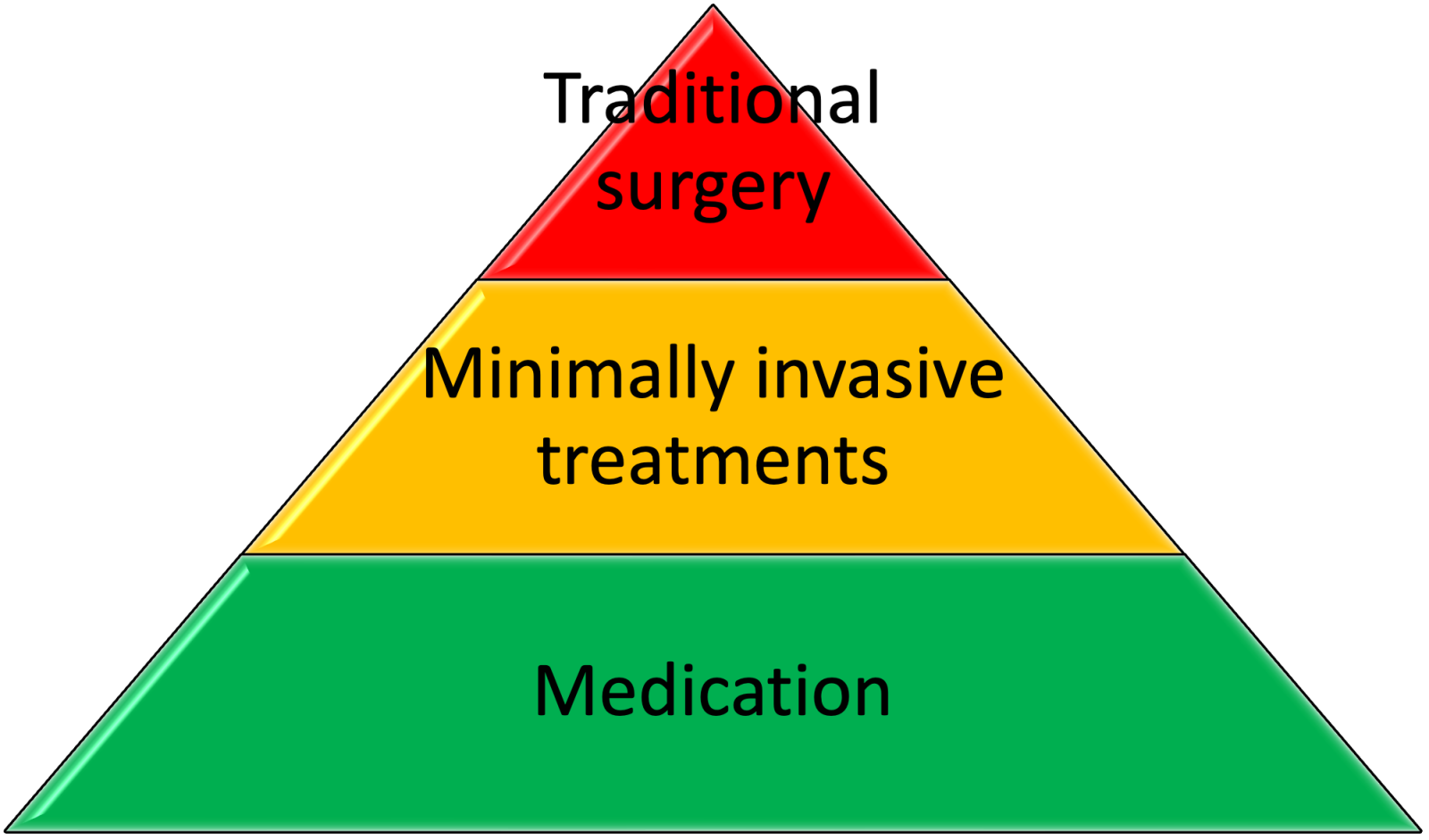

Figure 1. Treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia Figure 2. Prostatic urethral lift, showing implants being used to clear a channel through which urine can drain.

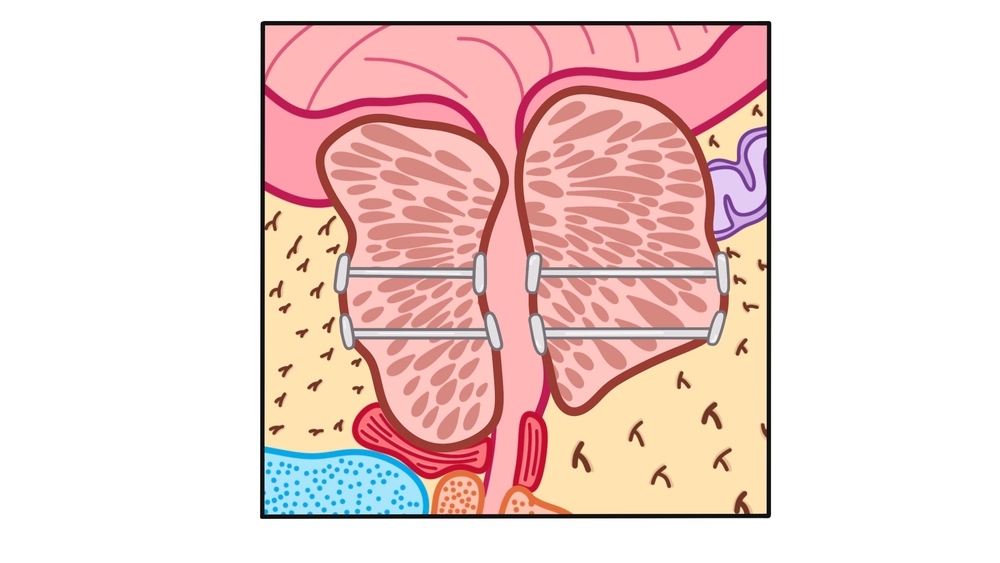

Figure 2. Prostatic urethral lift, showing implants being used to clear a channel through which urine can drain.  Figure 3. Prostate artery embolisation, using embolising agents to block prostatic blood vessels and cause the prostate to shrink.

Figure 3. Prostate artery embolisation, using embolising agents to block prostatic blood vessels and cause the prostate to shrink.