References

Berry AK (2006) Helping children with nocturnal enuresis: the wait-and-see approach may not be in anyone’s best interests. Am J Nurs 106: 56–63

Chang SJ, Van Laecke E, Bauer SB, von Gontard A, Bagli D, Bower WF, Renson C, Kawauchi A, Yang SS (2017) Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: A standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 36(1): 43–50

Grzeda MT, Heron J, von Gontard A, Joinson C (2017) Effects of urinary incontinence on psychosocial outcomes in adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 26(6): 649–58

Hellström AL, Hanson E, Hansson S, et al (1995) Micturition habits and incontinence at age 17 — reinvestigation of a cohort studied at age 7. Br J Urol 76: 231–4

Heron J, Grzeda MT, von Gontard A, Wright A, Joinson C (2017) Trajectories of urinary incontinence in childhood and bladder and bowel symptoms in adolescence: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 7(3): e014238

Hjälmas K (1992) Functional daytime incontinence: definitions and epidemiology. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 141: 39–46

NHS England (2018) Excellence in Continence Care: Practical guidance for commissioners, and leaders in health and social care. Available online: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/excellencein-continence-care.pdf

Schäfer SK, Niemczyk J, von Gontard A, et al (2018) Standard urotherapy as first-line intervention for daytime incontinence: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(8): 949–64

Swithinbank LV, Brookes ST, Shepherd AM, et al (1998) The natural history of urinary symptoms during adolescence. Br J Urol 81(Suppl 3): 90–3

Web T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie, S (2010) Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 12(1): e4

Whale K, Cramer H, Joinson C (2018) Left behind and left out: The impact of the school environment on young people with continence problems. Br J Health Psychol 23(2): 253–77

Whale K, Cramer H, Wright A, Sanders C, Joinson C (2017) ‘What does that mean?’: a qualitative exploration of the primary and secondary clinical care experiences of young people with continence problems in the UK. BMJ Open 7(10): e015544

Yeung CK, Sreedhar B, Sihoe JD, et al (2006) Differences in characteristics of nighttime enuresis between children and adolescents: a critical appraisal from a large epidemiological study. BJU Int 97: 1069–73

Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I (2015) The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 17(1): e30

Chang SJ, Van Laecke E, Bauer SB, von Gontard A, Bagli D, Bower WF, Renson C, Kawauchi A, Yang SS (2017) Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: A standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 36(1): 43–50

Grzeda MT, Heron J, von Gontard A, Joinson C (2017) Effects of urinary incontinence on psychosocial outcomes in adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 26(6): 649–58

Hellström AL, Hanson E, Hansson S, et al (1995) Micturition habits and incontinence at age 17 — reinvestigation of a cohort studied at age 7. Br J Urol 76: 231–4

Heron J, Grzeda MT, von Gontard A, Wright A, Joinson C (2017) Trajectories of urinary incontinence in childhood and bladder and bowel symptoms in adolescence: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 7(3): e014238

Hjälmas K (1992) Functional daytime incontinence: definitions and epidemiology. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 141: 39–46

NHS England (2018) Excellence in Continence Care: Practical guidance for commissioners, and leaders in health and social care. Available online: www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/excellencein-continence-care.pdf

Schäfer SK, Niemczyk J, von Gontard A, et al (2018) Standard urotherapy as first-line intervention for daytime incontinence: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(8): 949–64

Swithinbank LV, Brookes ST, Shepherd AM, et al (1998) The natural history of urinary symptoms during adolescence. Br J Urol 81(Suppl 3): 90–3

Web T, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie, S (2010) Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res 12(1): e4

Whale K, Cramer H, Joinson C (2018) Left behind and left out: The impact of the school environment on young people with continence problems. Br J Health Psychol 23(2): 253–77

Whale K, Cramer H, Wright A, Sanders C, Joinson C (2017) ‘What does that mean?’: a qualitative exploration of the primary and secondary clinical care experiences of young people with continence problems in the UK. BMJ Open 7(10): e015544

Yeung CK, Sreedhar B, Sihoe JD, et al (2006) Differences in characteristics of nighttime enuresis between children and adolescents: a critical appraisal from a large epidemiological study. BJU Int 97: 1069–73

Yardley L, Morrison L, Bradbury K, Muller I (2015) The person-based approach to intervention development: application to digital health-related behavior change interventions. J Med Internet Res 17(1): e30

Dr Carol Joinson (left), reader in developmental psychology, Centre for Academic Child Health, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol; Dr Katie Whale (right), health psychologist, research fellow in qualitative health research, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol

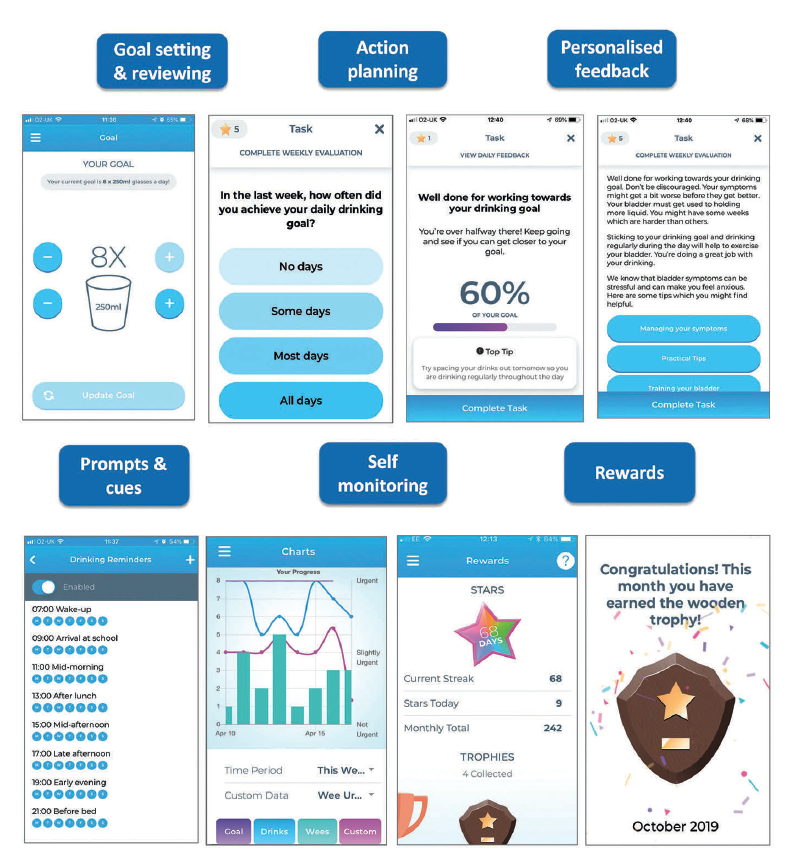

Dr Carol Joinson (left), reader in developmental psychology, Centre for Academic Child Health, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol; Dr Katie Whale (right), health psychologist, research fellow in qualitative health research, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol Figure 1.

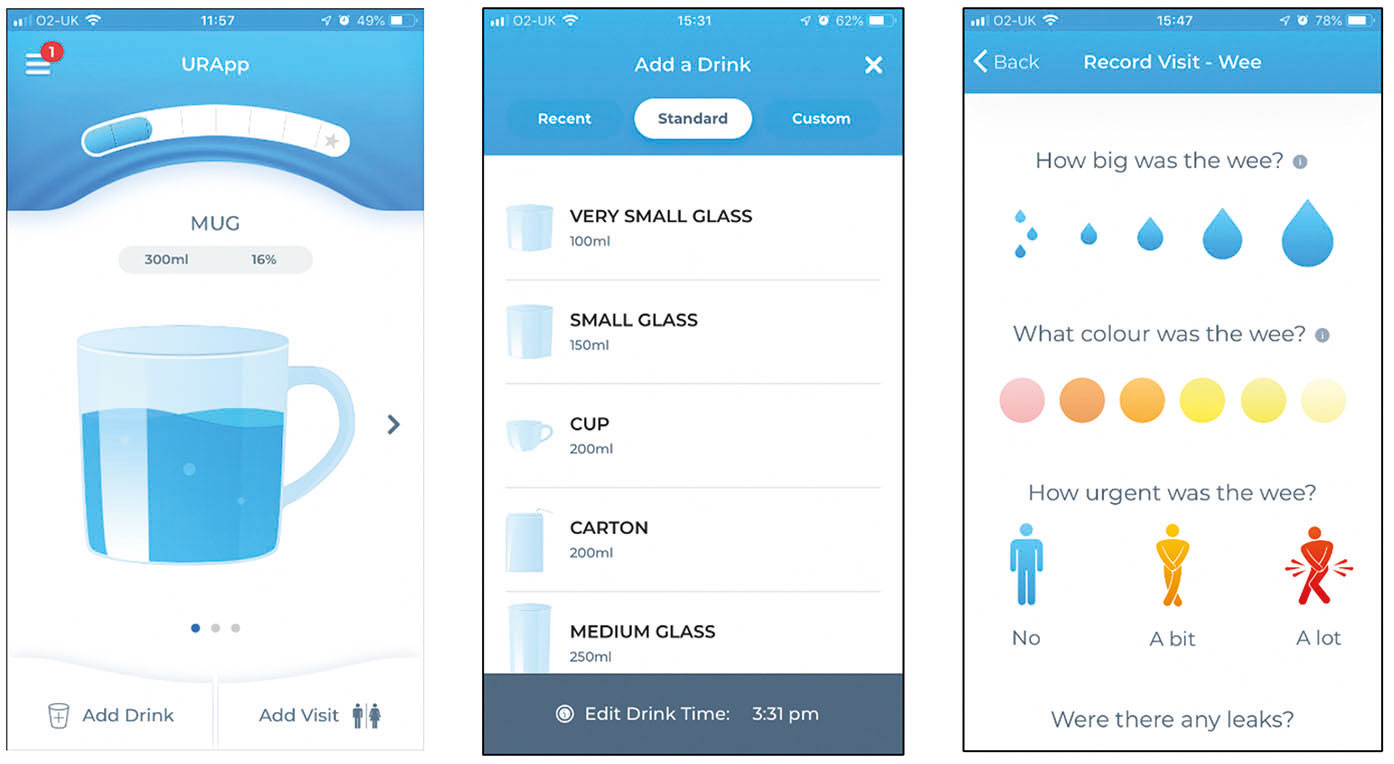

Figure 1. Figure 2.

Figure 2.