References

Association for Continence Advice (2021) Guidance for the provision of absorbent pad products for adult incontinence. A consensus document. Available online: https://www.aca.uk.com/application/files/8216/2220/2409/Product_Guidance_April_2021.pdf

Carr S (2019) Catheter valves: retraining the bladder to avoid prolonged catheter use. J Community Nurs 33(3): 46–51

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2016) National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Overview. Urinary tract infection (catheter-associated urinary tract infection [CAUTI] and non-catheter-associated urinary tract infection [UTI]) and other urinary system infection [USI]) events

Emmanuel AV, Krogh K, Bazzocchi G, et al (2013) Consensus review of best practice of transanal irrigation in adults. Spinal Cord 51(10): 732–8

Fader M, Cottenden A, Chatterton C, et al (2020) An International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for single use body worn absorbent incontinence products. Neurol Urodyn 39: 2031–39

Henderson M,Tinkler L,Yiannakou Y (2018) Transanal irrigation as a treatment for bowel dysfunction. Gastrointestinal Nurs 6(4): 26–34

International Continence Society (2017) Incontinence, 6th edn. Available online: www.ics.org/education/icspublications/icibooks/6thicibook

Lemmens JMH, Broadbridge J, Macaulay M, Rees RW, Archer M, Drake MJ, et al (2019) Tissue response to applied loading using different designs of penile compression clamps. Med Devices 12: 235–43

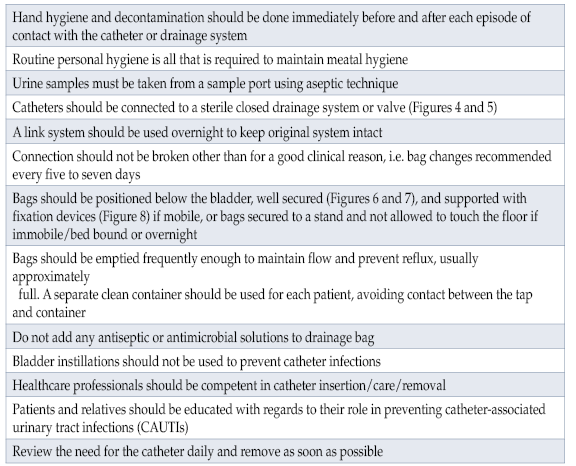

Loveday H, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ, et al (2014) epic3: National evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect 86: S1–70

Macaulay M, Broadbridge J, Gage H, Williams P, Birch B, Moore KN, Cottenden A, Fader M (2015) A trial of devices for urinary incontinence after treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int 116: 432–42

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018) Peristeen transanal irrigation system for managing bowel dysfunction. Medical technologies guidance MTG36. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg36

Royal College of Nursing (2021) Catheter Care. RCN Guidance for Professionals. Clinical Professional resource. RCN, London

Simpson P (2017) Long-term urethral catheterisation: guidelines for community nurses. Br J Nurs 26(9 Suppl): S22–S26

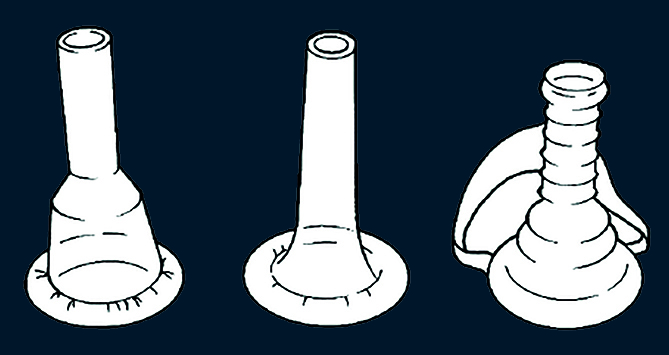

Smart C (2014) Male urinary incontinence and the urinary sheath. Br J Nurs 23(9): S20–S25

Soliman Y, Meyer R, Baum MD (2016) Falls in the elderly secondary to urinary symptoms. Rev Urol 18(1): 28–32

Yates A (2016) Indwelling urinary catheterisation: What is best practice? Br J Nurs 25(9): 2–7

Yates A (2017) Urinary catheters 4: teaching intermittent self-catheterisation. Nurs Times 113(4): 49–51

Yates A (2018) Catheter securing and fixation devices: their role in preventing complications. Br J Nurs 27(4): 2–4

Yates A (2019a) Indwelling urinary catheterisation: current best practice. J Community Nurs 32(2): 44–50

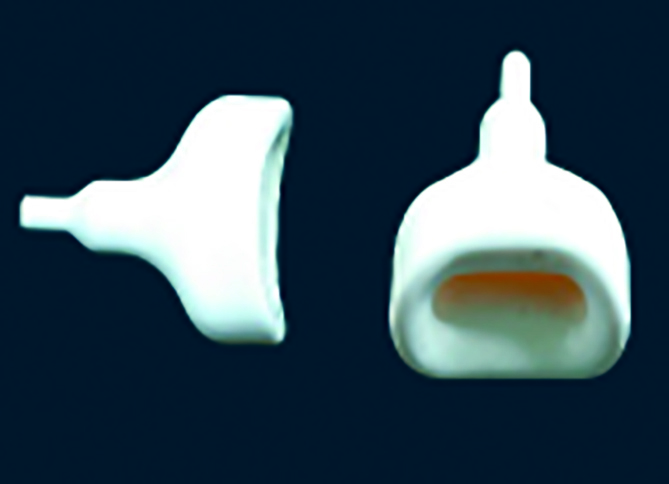

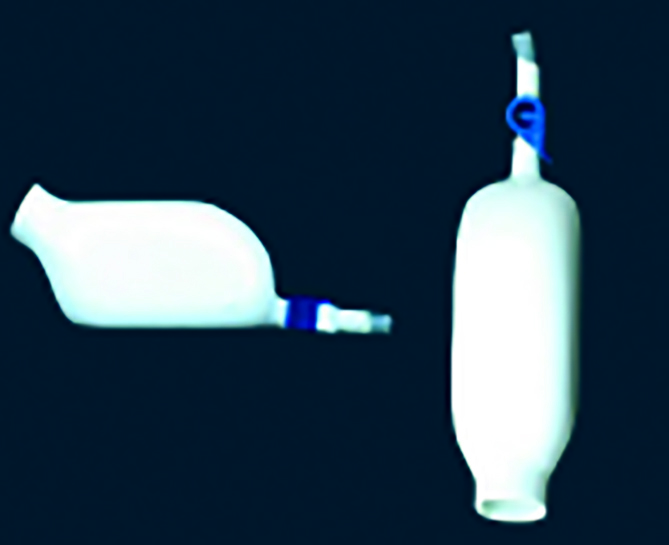

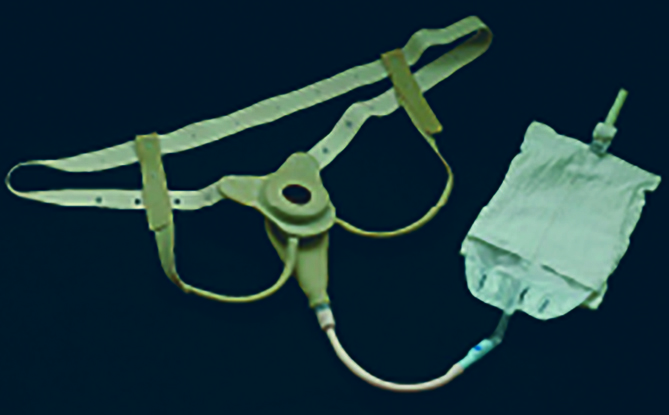

Yates A (2019b) Managing male urinary incontinence with sheaths, body worn urinals and penile compression clamps. J Community Nurs 33(5): 40–4

Yates A (2019c) Transanal irrigation: is it the magic intervention for bowel management in individuals with bowel dysfunction? Br J Nurs 29(7): 2–6

This piece was first published in the Journal of Community Nursing. To cite this article use: Yates A (2021) Clinical skills. Part 4: Management with appropriate devices/products. J Community Nurs 35(6): 20-26