References

Chen CH, Lee MH, Chen YC, Lin MF (2011) Ketamine-snorting associated cystitis. J Formosan Med Assoc 110: 787–91

Chu PS, Ma WK, Wong SC, et al (2008) The destruction of the lower urinary tract by ketamine abuse: a new syndrome? Br J Urol Int 102: 1616–22

Chung SD, Wang CC, Kuo HC (2014) Augmentation enterocystoplasty is effective in relieving refractory ketamine-related bladder pain. Neurourol Urodynamics 33(8): 1207–11

Cullen KR, Amatya P, Roback MG, Albott CS, Westlund Schreiner M, Ren Y, et al (2018) Intravenous ketamine for adolescents with treatment-resistent depression: an open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 28(7): 1–8

Daly M (2016) How ketamine has made its way back into the UK. Vice. Available online: www.vice.com/en_uk/article/ bnp48a/return-of-ketamine-uk-chinalabs

DrugScope (2006) Street drug prices 2006. Drugslink 21: 26. Available online: www. drugwise.org.uk/druglink-factsheet-2006- street-drug-prices-2006/factsheet-streetdrug- prices-2006/

DrugWise (2018) Ketamine: What is ketamine? Available online: www. drugwise.org.uk/ketamine/

Frank (2018) Ketamine. Available online: www.talktofrank.com/drug/ketamine

Jhang JF, Hsu YH, Kuo HC (2015) Possible pathophysiology of ketamine related cystitis and associated treatment strategies. Int J Urol 22: 816–25

Li JH, Vicknasingam B, Cheung YW, Zhou W, Wibowo Nurhidayat A, Jarlais DCD, Schottenfeld R (2011) To use or not to use: an update on illicit ketamine use. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2: 11–20

Logan K (2011) Addressing Ketamine bladder syndrome. Nurs Times 107: 24. Available online: www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladdersyndrome/5031324.article

Logan K, Gill P, Shaw C, John B, Madden K ( 2015 ) Users experiences of ketamine bladder syndrome. Neurological Urodynam 34(S3): 47–8

Mak SK, Chan MTY, Bower WF,Yip SKH, Hou SSM, Wu BBB, Man CY (2011) Lower urinary tract changes in young adults using ketamine. J Urol 186(2): 610–14

Mason K, Cottrell AM, Corrigan AG, Gillatt DA, Mitchelmore AE (2010) Ketamineassociated lower urinary tract destruction: a new radiological challenge. Clin Radiol 65(10): 795–800

Misra S (2018) Ketamine-associated bladder dysfunction: a review of the literature. Curr Bladder Dysfunction Reports 13(1): 1–8

Morgan CJ, Curran H V (2011) Ketamine use: a review. Addiction 107: 27–38

NHS Digital (2018) Statistics on Drugs Misuse: England 2018 (PAS). Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-andinformation/publications/statistical/statistics-on-drug-misuse/2018

Niesters M, Martini C, Dahan A (2013) Ketamine for chronic pain: risks and benefits. Br J Clin Pharmacol 77(2): 357–67

Ng CF, Chiu PK, Li ML, Man Cw, Hou SSM, Chan ESY, Chu PSK (2013) Clinical outcomes of augmentation cystoplasty in patients suffering from ketamine-related bladder contractures. Int Urol Nephrol 45(5): 1245–51

Ng SH, Tse ML, NG HW, Lau FL (2010) Emergency department presentation of ketamine abusers in Hong Kong: a review of 233 cases. Hong Kong Med J 16: 6–11

Sihra N, Rajendran S, Ockrim J, Wood D (2017a) Does the use of recreational ketamine pose a challenge on bladder reconstruction? Eur Urol Supplement 16(3): e2003. Available online: www. eusupplements.europeanurology.com/article/S1569-9056(17)31202-2/abstract

Sihra N, Ockrim J, Wood D (2017b) The effects of recreational ketamine cystitis on urinary tract reconstruction — a surgical challenge. Br J Urol Int 121: 458–65

Wilkinson ST, Katz RB, Toprak M, Webler R, Ostroff RB, Sanacora G (2018) Acute and longer-term outcomes using ketamine as a clinical treatment at the Yale Psychiatirc Hospital. J Clin Psychiatry 79(4): pii: 17m11731

Winstock AR, Mitcheson L, Gillatt DA, Cottrell AM (2012) The prevalence and natural history of urinary symptoms among recreational ketamine users. Br J Urol Int 110: 1762–66

Wood D, Cottrell A, Baker SC, Southgate J, Harris M, Fulford S, Woodhouse C, Gillett D (2011) Recreational ketamine: from pleasure to pain. Br J Urol Int 107: 1881–84

World Health Organization (2016) Fact file on ketamine. WHO, Geneva. Available online: www.who.int/medicines/news/20160309_FactFile_Ketamine.pdf

Zeng J, Lai H, Zheng D, Zhong L, Huang Z, Wang S, Zou W, Wei L (2017) Effective treatment of ketamine-associated cyctitis with botulinum toxin type A injection combined with bladder hydrodistention. J Int Med Res 45(2): 729–97

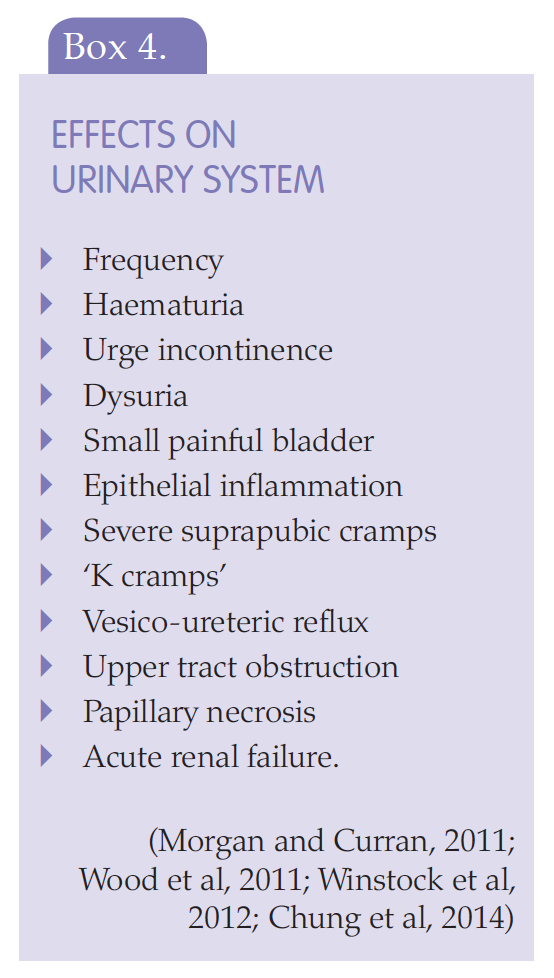

Patients who have reduced bladder capacity, thickened bladder walls and hydronephrosis (swelling of the pelvis of the kidney as a result of build up of urine) do not usually recover function, even if they stop taking the drug (Jhang et al, 2015). Patients may need ureteric stents or a nephrostomy tube inserting if there is obstruction or reflux to the kidney to allow urine to drain and relieve hydronephrosis, preserve renal function and stop further irreversible damage (Chu et al, 2008; Jhang et al, 2015).

Patients who have reduced bladder capacity, thickened bladder walls and hydronephrosis (swelling of the pelvis of the kidney as a result of build up of urine) do not usually recover function, even if they stop taking the drug (Jhang et al, 2015). Patients may need ureteric stents or a nephrostomy tube inserting if there is obstruction or reflux to the kidney to allow urine to drain and relieve hydronephrosis, preserve renal function and stop further irreversible damage (Chu et al, 2008; Jhang et al, 2015).