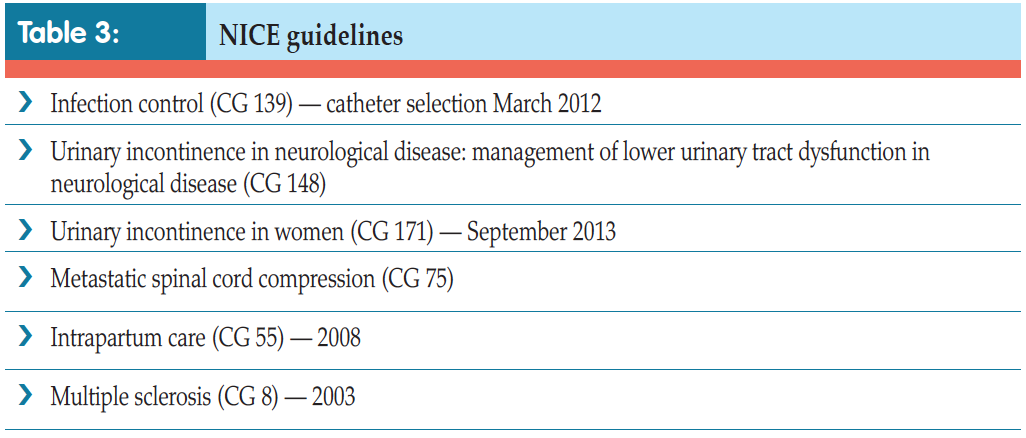

Over the last few decades, the use of intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) to control or assist voiding has become widespread. Increasingly, more treatments, both medical and surgical, are possible because of ISC. Alongside this increase in use has been the development and evolution of intermittent catheters themselves. There are also a number of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines advocating the use of ISC (Table 3). Of course, there will always be patients who cannot or will not perform ISC on themselves, either because of physical, practical or psychological impediments; however, it is equally true that not all patients who could benefit from using ISC are necessarily being offered it (Dingwall and McLafferty, 2006).

Lapides et al first published their findings on ISC in 1972, which showed that the procedure was associated with less urinary tract infections (UTIs) than indwelling catheterisation, and that it greatly improved the quality of life of patients with bladder problems. This 1972 paper and subsequent publications by Lapides et al (1974, 1976) and Diokno et al (1983) outlined the main advantages of ISC, which included:

Although not all patients are suitable for ISC, it is increasingly becoming an option, either as treatment or as a consequence of having surgery (Van Achterburg et al, 2007).

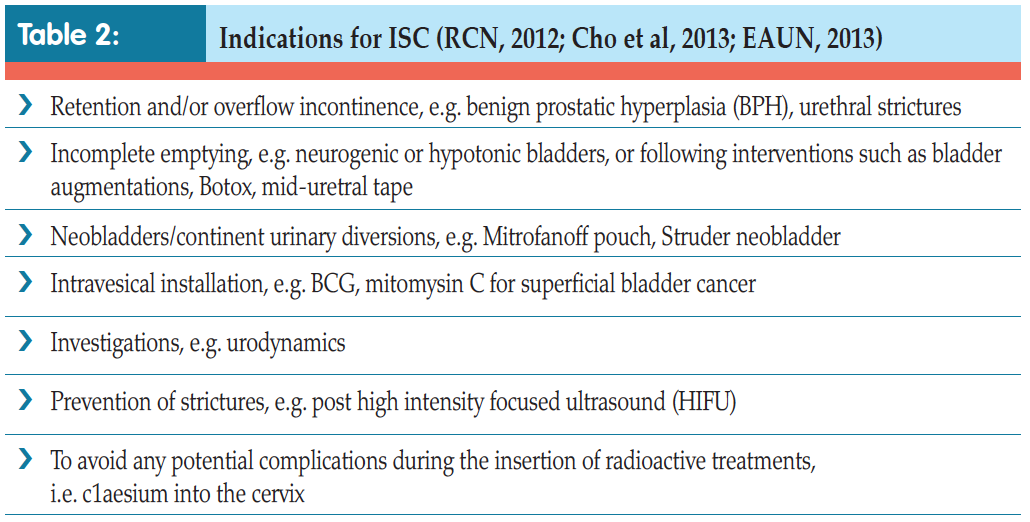

ISC is used to manage voiding for individuals with various problems, including those who, historically, were routinely managed with indwelling catheters for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or urethral strictures. Incomplete emptying, i.e. in neurogenic or hypotonic bladders, can also be successfully managed with ISC, as can that caused by surgical intervention such as Botox treatment for overactive bladders or following insertion of mid-urethral tape for urinary incontinence. Indeed, many surgical procedures which have become standard nowadays would not be possible without ISC. Continent urinary diversions, such as neobladders, enterocystoplasties, or urinary pouches, e.g. the Mitrofanoff, all rely on the patient being able to successfully self-catheterise to void (European Association of Urology Nurses [EAUN], 2013).

Other indications for the use of ISC include bladder or urethral investigations and intravesical instillation of drugs directly into the bladder, such as Bacillus Calmette– Guérin (BCG) vaccine or mitomycin for superficial bladder cancer (Bohle et al, 2003), or capsaisin for bladder overactivity (Kim and Chancellor, 2000).

It is also not suitable for accurate urine output monitoring, continuous bladder irrigation and immediately following surgery to the lower urinary tract, or where continuous drainage is required in high pressure bladders to avoid kidney damage (EAUN, 2013).

The principles governing ISC are the same as those for indwelling catheters in terms of how to do the procedure safely and to minimise risk to the patient. The main difference is that instead of the healthcare professional catheterising the patient aseptically, it is the patient who learns how to insert the catheter and drain the bladder using a clean rather than aseptic technique.

Research has shown that when done correctly, ISC is a safe procedure which avoids the problems associated with long-term indwelling catheters (Lapides et al, 1972; Igawa et al, 2008). Patients with indwelling catheters are at risk of UTIs, encrustation, stone formation, bladder spasm, urine bypassing and consequent urine leakage and catheter blockage (Feneley et al, 2015). These problems arise because the catheter, which is a foreign body, is usually left in the bladder for long periods of time (4–12 weeks). With ISC, the dwell time in the bladder is only a matter of minutes until all the urine has been drained away, after which the catheter is removed and discarded. This results in less risk of infection and all the consequent problems associated with it. Another advantage is that the patient does not need a permanently placed appliance, or have to deal with an external urine drainage bag, thus reducing the impact of catheterisation on quality of life and allowing the patient to be in control (Igawa et al, 2008; RCN, 2012; EAUN, 2015).

Lapides et al first published their findings on ISC in 1972, which showed that the procedure was associated with less urinary tract infections (UTIs) than indwelling catheterisation, and that it greatly improved the quality of life of patients with bladder problems. This 1972 paper and subsequent publications by Lapides et al (1974, 1976) and Diokno et al (1983) outlined the main advantages of ISC, which included:

- Preventing or overcoming infection by regular emptying of the bladder

- No real increased infection rate using a clean rather than a sterile procedure

- Promoting a ‘normal’ pattern of filling and emptying stages of micturition

- Protecting the upper urinary tract

- Improving symptoms

- Promoting independence

- Improving quality of life.

INTERMITTENT CATHETERISATION

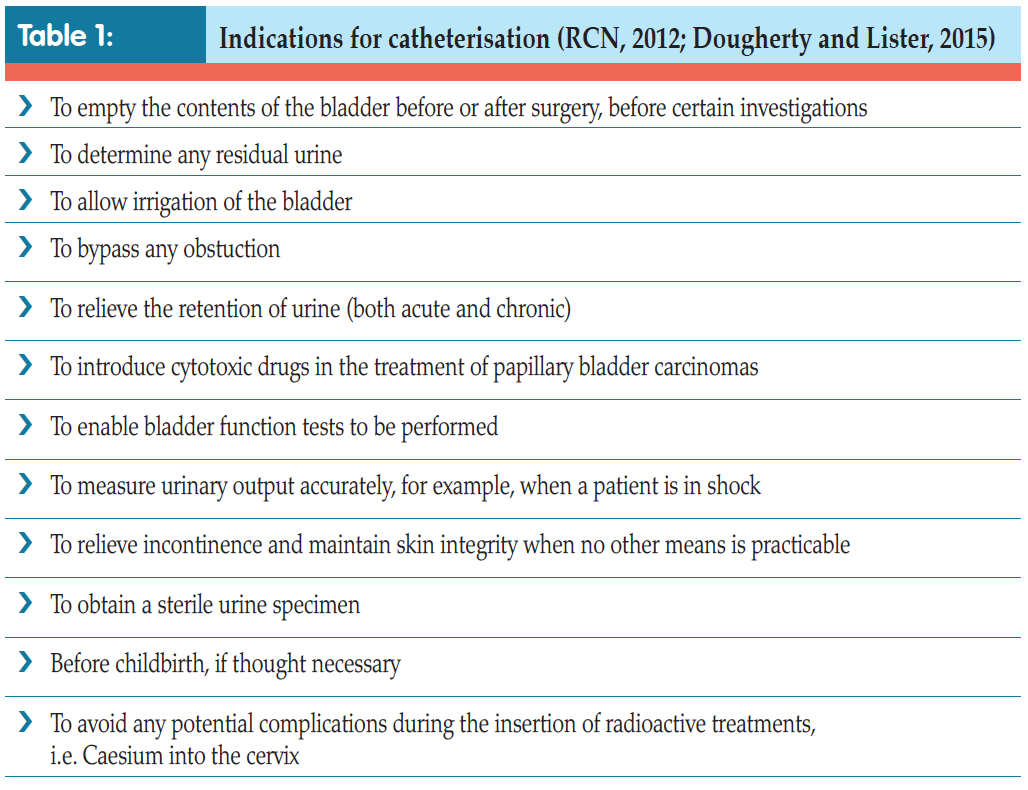

Indications

There are several indications for using catheters — both indwelling (see pp. 28–34) and intermittent (Tables 1 and 2).Although not all patients are suitable for ISC, it is increasingly becoming an option, either as treatment or as a consequence of having surgery (Van Achterburg et al, 2007).

ISC is used to manage voiding for individuals with various problems, including those who, historically, were routinely managed with indwelling catheters for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or urethral strictures. Incomplete emptying, i.e. in neurogenic or hypotonic bladders, can also be successfully managed with ISC, as can that caused by surgical intervention such as Botox treatment for overactive bladders or following insertion of mid-urethral tape for urinary incontinence. Indeed, many surgical procedures which have become standard nowadays would not be possible without ISC. Continent urinary diversions, such as neobladders, enterocystoplasties, or urinary pouches, e.g. the Mitrofanoff, all rely on the patient being able to successfully self-catheterise to void (European Association of Urology Nurses [EAUN], 2013).

Other indications for the use of ISC include bladder or urethral investigations and intravesical instillation of drugs directly into the bladder, such as Bacillus Calmette– Guérin (BCG) vaccine or mitomycin for superficial bladder cancer (Bohle et al, 2003), or capsaisin for bladder overactivity (Kim and Chancellor, 2000).

Contraindications and precautions

ISC is contraindicated in patients with a false passage down the urethra, those who have had trauma to the penis, or have a tumour or other injury. It should be used with caution following prostatic or urethral and bladder surgery, in patients with urethral stents or artificial prosthesis, or those with a tendency to bleed (Royal College of Nursing [RCN], 2012).It is also not suitable for accurate urine output monitoring, continuous bladder irrigation and immediately following surgery to the lower urinary tract, or where continuous drainage is required in high pressure bladders to avoid kidney damage (EAUN, 2013).

ISC versus indwelling catheters

ISC versus indwelling catheters

The principles governing ISC are the same as those for indwelling catheters in terms of how to do the procedure safely and to minimise risk to the patient. The main difference is that instead of the healthcare professional catheterising the patient aseptically, it is the patient who learns how to insert the catheter and drain the bladder using a clean rather than aseptic technique.Research has shown that when done correctly, ISC is a safe procedure which avoids the problems associated with long-term indwelling catheters (Lapides et al, 1972; Igawa et al, 2008). Patients with indwelling catheters are at risk of UTIs, encrustation, stone formation, bladder spasm, urine bypassing and consequent urine leakage and catheter blockage (Feneley et al, 2015). These problems arise because the catheter, which is a foreign body, is usually left in the bladder for long periods of time (4–12 weeks). With ISC, the dwell time in the bladder is only a matter of minutes until all the urine has been drained away, after which the catheter is removed and discarded. This results in less risk of infection and all the consequent problems associated with it. Another advantage is that the patient does not need a permanently placed appliance, or have to deal with an external urine drainage bag, thus reducing the impact of catheterisation on quality of life and allowing the patient to be in control (Igawa et al, 2008; RCN, 2012; EAUN, 2015).

TEACHING ISC

In the author’s clinical experience, the key to successful ISC depends on three main factors:- Choice of the right patient

- Willingness of the patient to undertake the procedure

- How the patient is taught to do it.

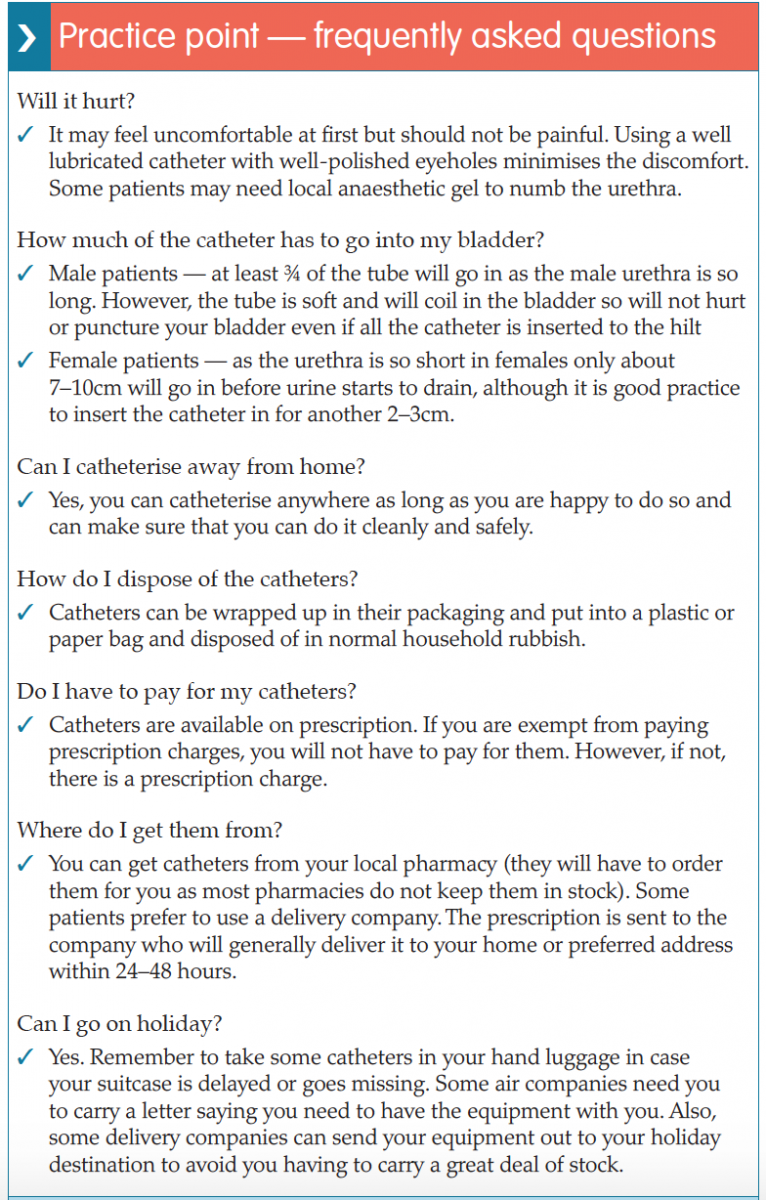

They also need to have enough physical ability and manual dexterity to handle the catheter and do the procedure cleanly, have reasonable bladder capacity, and the motivation and willingness to take ISC on for as long as needed, perhaps even for life. To help achieve the latter, it is important that ISC fits into the patient’s life and not the other way around, and that the procedure is kept simple and practical (RCN, 2012). If it negatively impacts on the patient’s day-to-day life, it is more likely that they will not stick to their regimen, which may mean a return of some of their symptoms and/or damage to the upper urinary tract (Shaw et al, 2008; RCN, 2012).

Therefore, it is important that nurses undertake a thorough assessment to establish the patient’s knowledge and ability, as well as their motivation. Patients need to 2012; EAUN, 2013):

- Their anatomy

- Why ISC needs to be done and how it will change their symptoms

- The principles of ISC -- what it involves and the importance of carrying out a clean procedure

- How often it needs to be done and why

- How it will fit into their life

- What types of catheters are available

- How to dispose of used catheters

- How to store catheters safely

- What the most common problems or complications are and how to deal with them

- When they need to seek help.

Not surprisingly, patients found learning ISC daunting, and that it caused them fear, anxiety and embarrassment. Ideally, they wanted to be taught the skill in their home environment. The nurse’s attitude and communication skills were also important in creating a relaxed atmosphere to help alleviate embarrassment and anxiety and enable patients to retain information (Logan et al, 2008; Shaw et al, 2008). The key to keeping patients motivated is having healthcare professionals who are experienced and aware that patients need time and understanding, as well as a proper assessment of their condition and physical and cognitive abilities.

Thus, teaching ISC should be tailored to each individual. As said, the amount of time it will take to learn and be confident varies from person to person. However, some healthcare professionals have limited time and resources and may not be able to cater to individual needs (Logan, 2017). Unfortunately, this means that patients either get minimum teaching before being expected to start the procedure, or are not followed up once they do so. Patients may be rationed to one face-to-face slot for a scheduled amount of time (e.g. 15–30 minutes), and then followed up by phone. Teaching aids, such as DVDs, sent to patients ahead of appointments can help them to focus on learning the actual technique and so get the greatest benefit from their appointment with the healthcare professional (Logan, 2017).

Thus, teaching ISC should be tailored to each individual. As said, the amount of time it will take to learn and be confident varies from person to person. However, some healthcare professionals have limited time and resources and may not be able to cater to individual needs (Logan, 2017). Unfortunately, this means that patients either get minimum teaching before being expected to start the procedure, or are not followed up once they do so. Patients may be rationed to one face-to-face slot for a scheduled amount of time (e.g. 15–30 minutes), and then followed up by phone. Teaching aids, such as DVDs, sent to patients ahead of appointments can help them to focus on learning the actual technique and so get the greatest benefit from their appointment with the healthcare professional (Logan, 2017).Ideally, patients should be seen as often as they need until they are confident and competent.

Follow-up

Follow-up

Patients should always be followed up for a period of time. Indeed, time spent with patients at this stage means that they are more likely to comply with care and carry on with ISC (Logan et al, 2008). Adherence to treatment regimens has been found to be directly linked to the patient’s ability to actively accept the need for ISC by establishing early coping strategies, rather than being in denial and avoiding the topic (Shaw and Logan, 2013). Shaw and Logan (2013) also found that reinforcing the positives of ISC and highlighting how it will enable independence and control over bladder function helps patients to achieve a return of some sense of normality, helping them to maintain the integrity of their:

- Self-image

- Privacy

- Dignity

- Self-esteem

- Quality of life.

CHOOSING THE RIGHT CATHETER

When teaching ISC, it is vital to choose the right catheter for the patient (Shaw et al, 2008). It needs to be the right length, size and type to enable efficient emptying of the bladder without being too big and so causing trauma and pain on insertion. In other words, the right catheter is the smallest size possible to do the job. Most people find size 12 Charrière (Ch) or French (F) catheter small enough to reduce discomfort, while allowing emptying within a reasonable time. The measure Charrière or French relates to the external diameter of a catheter, e.g. size 12Ch or F catheter is 4mm in diameter. The fuller the bladder, the longer it takes to empty, so establishing a regimen to suit the patient’s lifestyle, while also reversing the symptoms and maintaining bladder and upper urinary tract health, is important (RCN, 2012). Patients should be given a choice of different catheters to try to make sure that they choose the right one for their needs (Bardsley, 2015; Logan, 2017).Intermittent catheters are known as Nelaton catheters. Standard length catheters are between 40–45cm long and these suit men who have a longer urethra, as well as women who prefer or need to use a longer catheter. Female catheters are usually 25cm long (Continence Product Advisor, 2018). However, there are shorter, compact female-specific catheters, which are between 7 and 9cm long, making them discrete to carry and easy to use.

Most ISC catheters are made of plastic (PVC), which is an inert substance and does not irritate the urethral mucosa. Catheters can also be made of silicone or ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), and there may be some patients, although this is not common, who need to use stainless steel catheters (usually female patients), because these are more rigid and suit their needs (EAUN, 2013).

How catheters are manufactured affects the discomfort and trauma they may cause to the urethra. Nelaton catheters have a soft rounded tip and two lateral eyes (holes) at the tip through which urine drains. These eyes can cause discomfort and trauma if their edges are not smooth. Ideally, these should be cut into the catheter before it is polished in the manufacturing process, which will ‘round’ off the edges of the holes, making them smooth to touch. There are now also some catheters which have four holes instead of two. This speeds up drainage of urine and is particularly useful when emptying neobladders or enterocystoplasties, which tend to contain debris and mucus as well as urine and may easily block a catheter (Fillingham and Douglas, 2004).

Lubrication

Catheters also need lubrication to minimise friction and trauma on insertion (Bardsley, 2015). Patients may choose uncoated/unlubricated catheters, which can then be lubricated using gel before use. The gel is often supplied in the packet with the catheter or can be bought separately. Alternatively, some catheters are coated with a special hydrophyllic surface layer, which is activated by water or moisture. Most are made to allow the user to open the packet and add either tap water or the water supplied with the catheter itself. The latter has the advantage that a patient does not need to be around water to lubricate the catheter, thus making the procedure more flexible. There are also pre-lubricated catheters, which are packaged laying in a wet solution, thus eliminating the need for additional water or saline (EAUN, 2013).

Currently, all intermittent catheters are single-use only. If inserting the catheter is difficult, patients should be advised to try a different type. Different brands of catheter may feel softer and more

'... patients may need the self-lubricating catheters attached to bags by day to ensure that they can empty their bladder wherever they are, for example, if there is no disabled toilet they can access, but then use ones without a bag when at home.'

pliable or stiffer than others, despite being the same Charrière size. Catheters may also have different shaped tips, such as a tapered or olive tip, while some patients may require a catheter with a curved tip rather than a straight one (a Tiemann or Coude tip catheter). These can be useful if catheterisation is difficult, such as when trying to get past an enlarged prostate.

There are also catheters which are already attached to a urine drainage bag. This is especially useful when not in the vicinity of a toilet, or if the patient is in a wheelchair or cannot transfer onto the toilet for whatever reason. Here, urine drains directly into the bag and then can be disposed of later (EAUN, 2013).

A mixture of catheters can be used to suit different aspects of daily life. For example, patients may need the self-lubricating catheters attached to bags by day to ensure that they can empty their bladder wherever they are, for example, if there is no disabled toilet they can access, but then use ones without a bag when at home. There are also different aids available to help with dexterity or positioning issues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Aids to hold catheter in place or to allow a better grip.

Handling a catheter can be difficult, especially if it is selflubricating, as this layer tends to cover the full length of the catheter down to the end nozzle making it slippery. Nowadays, many manufacturers do not coat the catheter all the way down, but allow a few lubrication-free centimetres for a better grip. Some provide a plastic sleeve or grip around the catheter, which can be moved up or down the tube, allowing for it both to be gripped firmly as well as a no-touch technique. Female patients may use a mirror to visualise their urethra, although it can be difficult to hold or balance a mirror while catheterising (Logan, 2017). Using mirrors which are mounted on holders or leg spreaders that can be placed between the knees allowing two hands free for catheterisation can be useful. Similarly, male patients may benefit from using penis holders, while portable urinals for both men and women can also help with the process (Continence Product Advisor, 2018; Figure 1).

Male patients Most healthcare professionals ask patients to clean the urethal area with soap and water before ISC, although there is evidence that using water for general urogenital hygiene is sufficient (Bardsley, 2015). If away from home, a wet wipe may be used. Patients should then wash their hands and prepare the catheter for use, making sure that it does not touch any other surface which may contaminate it and taking care not to touch the tip or any part of the catheter that will be advanced into the bladder. Catheters that need lubrication or activation of a lubricating layer usually come with a little sticky pad at the top of the packet to allow this to stick to a surface, such as the side of a sink, thus freeing up both hands. In some cases, activation of the lubricating layer may take up to 30 seconds.

PERFORMING ISC

Patients are encouraged to find the position that is most comfortable and best suited for them to carry out ISC (Robinson, 2006). Most men will opt to stand over a toilet if able or sit facing it, for example, if in a wheelchair. Women tend to sit on a toilet, although some prefer to stand or sit on the side of a bath or bed.Male patients Most healthcare professionals ask patients to clean the urethal area with soap and water before ISC, although there is evidence that using water for general urogenital hygiene is sufficient (Bardsley, 2015). If away from home, a wet wipe may be used. Patients should then wash their hands and prepare the catheter for use, making sure that it does not touch any other surface which may contaminate it and taking care not to touch the tip or any part of the catheter that will be advanced into the bladder. Catheters that need lubrication or activation of a lubricating layer usually come with a little sticky pad at the top of the packet to allow this to stick to a surface, such as the side of a sink, thus freeing up both hands. In some cases, activation of the lubricating layer may take up to 30 seconds.

Male patients

Most healthcare professionals ask patients to clean the urethal area with soap and water before ISC, although there is evidence that using water for general urogenital hygiene is sufficient (Bardsley, 2015). If away from home, a wet wipe may be used. Patients should then wash their hands and prepare the catheter for use, making sure that it does not touch any other surface which may contaminate it and taking care not to touch the tip or any part of the catheter that will be advanced into the bladder. Catheters that need lubrication or activation of a lubricating layer usually come with a little sticky pad at the top of the packet to allow this to stick to a surface, such as the side of a sink, thus freeing up both hands. In some cases, activation of the lubricating layer may take up to 30 seconds.The penis should be grasped in one hand at an angle of 90 degrees to the body and the foreskin (if present) pulled back to expose the head of the penis and the external urethral opening. The catheter should be taken out of its packet and the tip gently inserted into the opening, then down the urethra. Patients may find this uncomfortable and frightening at first, and need reassurance to persevere. They should be asked to use gentle but firm pressure when inserting the catheter, and be prepared to feel some resistance when the catheter gets to the external sphincter area. It is important to encourage patients to relax the sphincter and continue it gets to the bladder when urine should start to drain. The catheter should be pushed in 3–5cm further to ensure it is definitely in the bladder. Once the flow slows, it can be gently withdrawn. Patients should be warned that as the catheter comes out more urine may drain. It is good practice to press gently on the suprapubic area to make sure all urine has drained and the bladder is completely empty. The catheter can then be removed and disposed of. This can usually be put into a plastic bag and disposed of in household rubbish. If there is a foreskin, this needs to be pulled back into place.

Female patients

The procedure is essentially the same except that it is a little bit more difficult for women to visualise their urethral opening and, in the author’s clinical experience, repeated failure to successfully catheterise in the early stages may reduce the patient’s confidence. It is important to reassure women that this is normal and that it will improve with practice. Finding a comfortable and practical position may take time. Using a mirror to locate the urethral opening can be helpful, although many women eventually stop using this and are able to insert the catheter successfully by touch. If the catheter is inadvertently inserted into the vagina, patients should be warned not to use the same catheter again as this will contaminate the bladder and may cause infection (Logan, 2017).Top tip

Nowadays, many manufacturers are producing catheters in discrete small packets, so ensuring privacy and making it more acceptable for people to be able to carry them around in bags without fear and embarrassment.

PROBLEMS IN CATHETERISATION

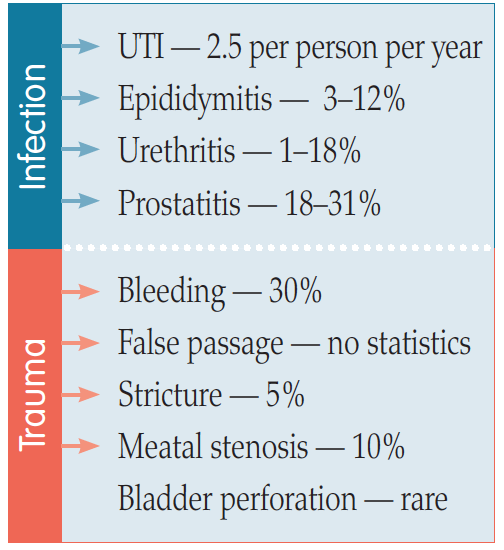

Although ISC causes less problems than indwelling catheters for patients, it is not trouble-free, which is why it is essential to ensure that patients have a good knowledge of what to do, and when to seek help should the need arise.

Difficulty inserting catheter

Catheter insertion may be difficult, either because of anatomical changes (e.g. following a prolapse, an enlarged prostate or postsurgery), or because of trauma from repeated catheterisation (e.g. urethral stricture or false passage). This may mean reassessing the patient’s technique and possibly using a different catheter to get past the obstruction, or referring back to the surgeon, especially if there is a stricture or false passage (EAUN, 2013).

Pain

Pain on insertion or removal of catheters can cause patients to avoid doing ISC regularly, or even at all (Barton, 2000; Mangall, 2013). Pain may be a result of the patient feeling tense and not completely relaxing the pelvic floor, and thus stopping the catheter going past the external sphincter and up to the bladder. Older women may also have mucosal atrophy and vaginal atrophy post menopause, making the area sensitive as they insert the catheter (Logan, 2017).Catheterisation may also trigger bladder spasm which causes pain. Again, the patient’s catheterisation technique should be reassessed and instruction on how to relax the pelvic floor may be beneficial. Local anaesthetic gel may also help, as well as trying different catheters, such as a softer catheter or one with a different lubricant. Anticholinergic medication can help with bladder spasms (Bardsley, 2015).

No urine draining

Occasionally, although the catheter is in the bladder, no urine drains out. If the bladder is not very full it may be that the patient is not in the correct position to ensure urine can drain through the catheter. This can be resolved by sitting up, leaning forward or gently inserting the catheter a little further in, or alternatively actually withdrawing it slightly until urine starts to drain. Sometimes the drainage holes may be blocked and need clearing if a lot of gel was used to lubricate the tube. Increasing intra-abdominal pressure by coughing or pressing down on the suprapubic area will force the gel down the catheter and the urine will follow.

Trouble removing catheter

Patients may experience difficulty in

removing a catheter. This happens

because as the bladder empties

rapidly the bladder collapses down,

and the inner wall of the bladder,

the mucosa, can get ‘sucked into’

the eyes of the catheter, which

effectively blocks it. When the

patient tries to pull the catheter

out, there is resistance because

the mucosa is caught in the holes.

Patients describe the catheter as

‘shuddering’ when this happens,

and should be instructed to wait a

few moments to allow the bladder

to relax, then slowly rotate the

catheter while gently pulling it out

(EAUN, 2013).

Bleeding

It is also important to reassure patients that some slight bleeding when the urine starts to drain, or some blood on the catheter tip when it is withdrawn, are normal, although prolonged and heavy bleeding is not (RCN, 2012). If this happens, they should seek help (Bardsley, 2015).

Leaking urine in between catheterisations

Some patients may still leak urine in-between catheterisations and again this may impact on their adhering to the treatment regimen. Asking the patient to keep a threeday diary of all their fluid input and urine output and indicating when they leak will give a picture of how often they are doing the procedure and if they are emptying the bladder properly. Again, they may need their technique reassessed to ensure that they are emptying properly and completely. It might mean that patients need to increase the number of times they catheterise during the day and adjust how much fluid, and when they drink it, during the day, to have longer dry spells. Once again, anticholinergic medication may help if the bladder is overactive and the leak is a result of bladder spasms (Barton, 2010; Mangnall, 2012).

Other complications

Other problems on immediate catheterisation include formation of a false passage and very rarely bladder perforation (especially in reconstructed bladders, such as neobladders or enterocystoplasties) and urethral strictures. There is still the possibility of chronic bacteriuria, although this is less so than with indwelling catheters. Other issues that might arise include epididymitis, urethritis and prostatitis. Patients can also produce bladder stones. This is rare, but can happen especially if the patient has a reconstructed bladder made of bowel and so has a lot of mucus sitting in the bladder, which is not drained out and/or washed out regularly (EAUN, 2013). Table 3 outlines NICE guidelines which advocate use of ISC in bladder care of certain patient groups.

Figure 2. Complications of ISC (EAUN, 2013).

PATIENT SCENARIO

Mr Fox, a 72-year-old retired teacher, presented in Accident and Emergency as he had been unable to pass urine for the past eight hours. On questioning, he admitted that since retiring from teaching at the age of 65, he had noticed that he passed urine more frequently and in smaller amounts during the day. His stream was weak and he rarely slept through the night without having to wake up four to five times to empty his bladder. This disturbed his wife, who had had to resort to sleeping in the spare room on occasion. Recently, he had also found that when he got the urge to pass urine it was difficult for him to hold on and occasionally he leaked urine before he got to the toilet. He had to wear a small male incontinence pad, which he found upsetting and embarrassing. This made him reluctant to leave the house, especially if he was going somewhere new or where he did not know what bathroom facilities would be available. He usually limited his outings to under two hours, as he would inevitably need to find a toilet quickly if he stayed out any longer. He had cut down his fluid intake in an attempt to produce less urine and to stop being ‘caught short’, but this did not seem to make any difference. If anything, his urgency had increased.Mr Fox was catheterised with an indwelling catheter and 2,500mls of urine was drained. He was discharged home with antibiotics to take for three days and given instructions on caring for his catheter. This was removed during a clinic appointment two weeks later. However, Mr Fox was unable to empty his bladder spontaneously and the catheter was reinserted and he subsequently failed a further trial without catheter. On discussion with his consultant, Mr Fox was reluctant to have surgery for his enlarged prostate and it was decided to start him on alpha blocker medication (Roehrborn and Schwinn, 2004), which would relax the smooth muscle of his bladder neck. He was also referred to the continence advisor to learn ISC. He opted to try this, as he was not keen to have a permanent indwelling catheter.

He was reviewed in clinic three months later and reported no problems with ISC. His urgency and frequency had subsided and he was now able to pass some urine spontaneously. However, he still did not empty completely and was doing ISC three times a day. He was dry and, most importantly, was sleeping throughout the night much to his wife’s relief.

CONCLUSION

Intermittent self-catheterisation is an intimate, invasive procedure which patients find challenging. It can cause anxiety and distress, especially because of the fear of possible pain on insertion (Logan, 2017). These barriers may impede patients’ ability to learn the technique and adhering to a catheterisation schedule.Teaching ISC can also pose a challenge to healthcare professionals. Research has shown that healthare professionals’ attitude, communication and teaching skills are key when it comes to helping patients accept the need to perform ISC, and learn how to do it safely and retain all the information needed to cope with problems as they arise (Shaw et al, 2008; Logan, 2017). Tailoring teaching to the individual needs of each patient and taking the time to ensure that they absorb the information and become confident and competent has been shown to increase the likelihood of patients being successful (Bardsley, 2015). Having a better understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of undertaking ISC enables healthcare professionals to better identify patients who would benefit from this technique, and so be referred for assessment and to learn how to do the procedure, as well as becoming knowledgeable and skilful enough to carry on using ISC safely in the long term. Healthcare professionals should also be aware of the possible difficulties and complications that may ensue, and be able to resolve problems to support patients and help them adhere to their treatment regimens.

References

Addison R, Foxley S, Mould W, et al (2012) Catheter care RCN guidance for nurses. RCN, London. Available online: http:// studyres.com/doc/8027570/cathetercare- rcn-guidance-for-nurses?page=2

Bardsley A (2015) ISC in women following urogynaecologic surgery. Br J Nurs (urology supplement) 20(18): S6–S13

Barton R (2000) Intermittent self catheterisation. Nurs Standard 15(9): 47–52

Bohle A, Jocham D, Bock PR (2003) Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus mitomycin C for superficial bladder cancer: a formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on recurrence and toxicity. J Urol 169(1): 90–5

Cho WJ, Kim TH, Lee HS, Chung JW, Lee HN, Lee KS (2013) Treatment of urethral/bladder neck stricture after high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer with holmium: yttriumaluminium- garnet laser. Int Neurourol J 17(1): 24–9

Continence Product Advisor (2018) Indwelling catheters. Available online: www.continenceproductadvisor.org/products/catheters/indwellingcatheters (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Dingwall L, McLafferty E (2006) Nurses’ perceptions of indwelling urinary catheters in older people. Nurs Standard 21(14): 35–42

Diokno Ac, Sonda LP, Hollander JB, Lapides J (1983) Fate of patients started on clean intermittent selfcatheterisation therapy 10 years ago. J Urol 129(6): 1120–2

Doughty L, Lister S (2015) The Royal Marsden Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures (Royal Marsden Manual Series). 9th edn. Elimination. Wiley- Blackwell, UK: chap 5

European Association of Urology Nurses (2013) Catheterisation: urethral intermittent in adults. Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Urological Health Care. EAUN. Available online: http://nurses.uroweb.org/guideline/catheterisation-urethral-intermittent-inadults (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Feneley R, Hopley I, Wells P (2015) Urinary catheters: history, current status, adverse events and research agenda. J Med Eng Technol 39(8): 459–70

Fillingham S, Douglas J, eds (2004) Urological Nursing. 3rd edn. Baillière Tindall, UK

Igawa Y, Wyndaele JJ, Nishizawa O (2008) Catheterization: Possible complications and their prevention and treatment. Int J Urol (15): 481–5

Kim DY, Chancellor MB (2000) Intravesical neuromodulatory drugs: capsaicin and resiniferatoxin to treat the overactive bladder. J Endourol 14(1): 97–103

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Silber SM, Lowe BS (1972) Clean intermittent selfcatheterisation in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol 107(3): 458–61

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Lowe BS, Kalish MD (1974) Follow-up on unsterile intermittent self-catheterisation. J Urol 111(2): 184–7

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Gould FR, Lowe BS (1976) Further observations on selfcatheterisation. J Urol 116(2): 169–71

Logan K, Shaw C, Webber I, Samuel S, Broome L (2008) Patients; experiences of learning clean intermittent selfcatheterisation: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 62(1): 32–40

Logan K (2017) The female experience of ISC with a silicone catheter. Br J Nurs 26(2): 82–8

Mangnall J (2013) Key considerations of intermittent self-catheterisation. Br J Nurs 21(7): 392–8

Robinson J (2006) Intermittent selfcatheterisation: principles and practice. Br J Community Nurs 11(4): 144–52

Roehrborn CG, Schwinn DA (2004) Alpha 1-adrenergic receptors and their inhibitors in lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 171: 1029–35

Royal College of Nursing (2012) Catheter Care: RCN Guidance for Nurses. RCN, London

Shaw C, Logan K (2013) Psychological coping with intermittent selfcatheterisation( ISC) in people with spinal injury: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 50(10): 1341–50

Shaw C, Logan K, Webber I, Broome L, Samuel S (2008) Effect of clean intermittent self-catheterisation on quality of life: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 61(6): 641–50

Urology textbook (2018) Anatomy of the Bladder. Available online: www.urologytextbook.com/bladder-anatomy.html (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Van Achterburg T, Holleman G, Cobussen-Boekhourst H, Arts R, Heesakkers J (2007) Adherence to clean intermittent catheterisation: determinants explored. J Clin Nurs 17(3): 394–402

Bardsley A (2015) ISC in women following urogynaecologic surgery. Br J Nurs (urology supplement) 20(18): S6–S13

Barton R (2000) Intermittent self catheterisation. Nurs Standard 15(9): 47–52

Bohle A, Jocham D, Bock PR (2003) Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus mitomycin C for superficial bladder cancer: a formal meta-analysis of comparative studies on recurrence and toxicity. J Urol 169(1): 90–5

Cho WJ, Kim TH, Lee HS, Chung JW, Lee HN, Lee KS (2013) Treatment of urethral/bladder neck stricture after high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer with holmium: yttriumaluminium- garnet laser. Int Neurourol J 17(1): 24–9

Continence Product Advisor (2018) Indwelling catheters. Available online: www.continenceproductadvisor.org/products/catheters/indwellingcatheters (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Dingwall L, McLafferty E (2006) Nurses’ perceptions of indwelling urinary catheters in older people. Nurs Standard 21(14): 35–42

Diokno Ac, Sonda LP, Hollander JB, Lapides J (1983) Fate of patients started on clean intermittent selfcatheterisation therapy 10 years ago. J Urol 129(6): 1120–2

Doughty L, Lister S (2015) The Royal Marsden Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures (Royal Marsden Manual Series). 9th edn. Elimination. Wiley- Blackwell, UK: chap 5

European Association of Urology Nurses (2013) Catheterisation: urethral intermittent in adults. Evidence-based Guidelines for Best Practice in Urological Health Care. EAUN. Available online: http://nurses.uroweb.org/guideline/catheterisation-urethral-intermittent-inadults (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Feneley R, Hopley I, Wells P (2015) Urinary catheters: history, current status, adverse events and research agenda. J Med Eng Technol 39(8): 459–70

Fillingham S, Douglas J, eds (2004) Urological Nursing. 3rd edn. Baillière Tindall, UK

Igawa Y, Wyndaele JJ, Nishizawa O (2008) Catheterization: Possible complications and their prevention and treatment. Int J Urol (15): 481–5

Kim DY, Chancellor MB (2000) Intravesical neuromodulatory drugs: capsaicin and resiniferatoxin to treat the overactive bladder. J Endourol 14(1): 97–103

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Silber SM, Lowe BS (1972) Clean intermittent selfcatheterisation in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol 107(3): 458–61

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Lowe BS, Kalish MD (1974) Follow-up on unsterile intermittent self-catheterisation. J Urol 111(2): 184–7

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Gould FR, Lowe BS (1976) Further observations on selfcatheterisation. J Urol 116(2): 169–71

Logan K, Shaw C, Webber I, Samuel S, Broome L (2008) Patients; experiences of learning clean intermittent selfcatheterisation: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 62(1): 32–40

Logan K (2017) The female experience of ISC with a silicone catheter. Br J Nurs 26(2): 82–8

Mangnall J (2013) Key considerations of intermittent self-catheterisation. Br J Nurs 21(7): 392–8

Robinson J (2006) Intermittent selfcatheterisation: principles and practice. Br J Community Nurs 11(4): 144–52

Roehrborn CG, Schwinn DA (2004) Alpha 1-adrenergic receptors and their inhibitors in lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol 171: 1029–35

Royal College of Nursing (2012) Catheter Care: RCN Guidance for Nurses. RCN, London

Shaw C, Logan K (2013) Psychological coping with intermittent selfcatheterisation( ISC) in people with spinal injury: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud 50(10): 1341–50

Shaw C, Logan K, Webber I, Broome L, Samuel S (2008) Effect of clean intermittent self-catheterisation on quality of life: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 61(6): 641–50

Urology textbook (2018) Anatomy of the Bladder. Available online: www.urologytextbook.com/bladder-anatomy.html (last accessed 30 January, 2018)

Van Achterburg T, Holleman G, Cobussen-Boekhourst H, Arts R, Heesakkers J (2007) Adherence to clean intermittent catheterisation: determinants explored. J Clin Nurs 17(3): 394–402