References

Adil S, Gordon M, Hathagoda W et al (2024) Impact of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour on functional constipation in children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMJ Paediatr Open. 8(1):e003069. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2024-003069

Al-Beltagi M, Saeed NK, Bediwy AS (2025) Exploring the gut-exercise link: A systematic review of gastrointestinal disorders in physical activity. World J Gastroenterol. 31(22): 106835. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i22.106835

Bashir SK, Khan MB (2024) Pediatric functional constipation: a new challenge. Advanced Gut Microbiome Research. 2024(1):5569563. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5569563

Chase J, Shields N (2011) A systematic review of the efficacy of non-pharmacological, non-surgical and non-behavioural treatments of functional chronic constipation in children. The Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal. 17(2):40-50

Chen K, Zhou Z, Nie S et al (2024) Adjunctive efficacy of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis XLTG11 for functional constipation in children. Braz J Microbiol. 55(2):1317-1330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-024-01276-3

de Geus A, Koppen LJN, Flin RB et al (2023) An update of pharmacological management in children with functional constipation. Pediatric Drugs. 25:343–358 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-023-00563-0

Dierkes J, Nwaru BI, Ramel A et al (2023) Dietary fiber and growth, iron status and bowel function in children 0-5 years old: a systematic review. Food Nutr Res. 67. https://doi.org/10.29219/fnr.v67.9011

Doğan İG, Gürşen C, Akbayrak T et al (2022) Abdominal massage in functional chronic constipation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys Ther. 102:pzac058. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac058

Ellis MR, Meadows S (2002) Clinical inquiries. What is the best therapy for constipation in infants? J Fam Pract. 51(8):682

Erdogan A, Rao S, Thiruvaiyaru D et al (2016) Randomized clinical trial: soluble/insoluble fiber or psyllium for chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 44(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13647

Gearry R, Fukudo S, Barbara G et al (2023) Consumption of 2 green kiwifruits daily improves constipation and abdominal comfort—results of an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 118:1058–1068. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002124

Hozyasz K (2023) Dietetic treatment of functional constipation in children: a scoping review with narrative summary [Polish]. Long-Term Care Nursing. 8(1):34-55. https://doi.org/10.19251/pwod/2023.1(4)

Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M (2016) Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 150(6):1456–1468.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015

Iacona R, Ramage L, Malakounides G (2019) Current state of neuromodulation for constipation and fecal incontinence in children: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 29(6):495-503. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1677485

Jarzebicka D, Sieczkowska J, Dadalski M, Kierkus J, Ryzko J, Oracz G (2016) Evaluation of the effectiveness of biofeedback therapy for functional constipation in children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 27(5):433-438. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2016.16140

Koyama T, Nagata N, Nishiura K, Miura N, Kawai T, Yamamoto H (2022) Prune juice containing sorbitol, pectin, and polyphenol ameliorates subjective complaints and hard feces while normalizing stool in chronic constipation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 117(10):1714-1717. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001931

Lee-Robichaud H, Thomas K, Morgan J et al (2010) lactulose versus polyethylene glycol for chronic constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (7):CD007570. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007570.pub2

Leung AKC, Hon KL (2021) Paediatrics: how to manage functional constipation. Drugs in Context. 10: 2020-11-2. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2020-11-2

Levy EI, Lemmens R, Vandenplas Y, Devreker T (2017) Functional constipation in children: challenges and solutions. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 8:19-27. https://doi.org/10.2147/PHMT.S110940

Liu Z, Gang L, Yunwei M, Lin L (2021) Clinical efficacy of infantile massage in the treatment of infant functional constipation: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 9:663581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.663581

Malekiantaghi A, Miladi M, Ostadan MT et al (2025) Abdominal massage as an adjunctive therapy for pediatric functional constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Turk J Pediatr. 67(5):669-677. https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjpediatr.2025.6367

Mulhem E, Khondoker F, Kandiah S (2022) Constipation in children and adolescents: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 105(5):469-478

Narula Khanna H, Roy S, Shaikh A et al (2025) Impact of probiotic supplements on behavioural and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr Open. 9(1):e003045. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2024-003045

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. CG99. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99/chapter/Recommendations#clinical-management (accessed 6 November 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2025) Constipation in children: choice of laxatives. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/constipation-in-children/prescribing-information/choice-of-laxatives/ (accessed 13 November 2025)

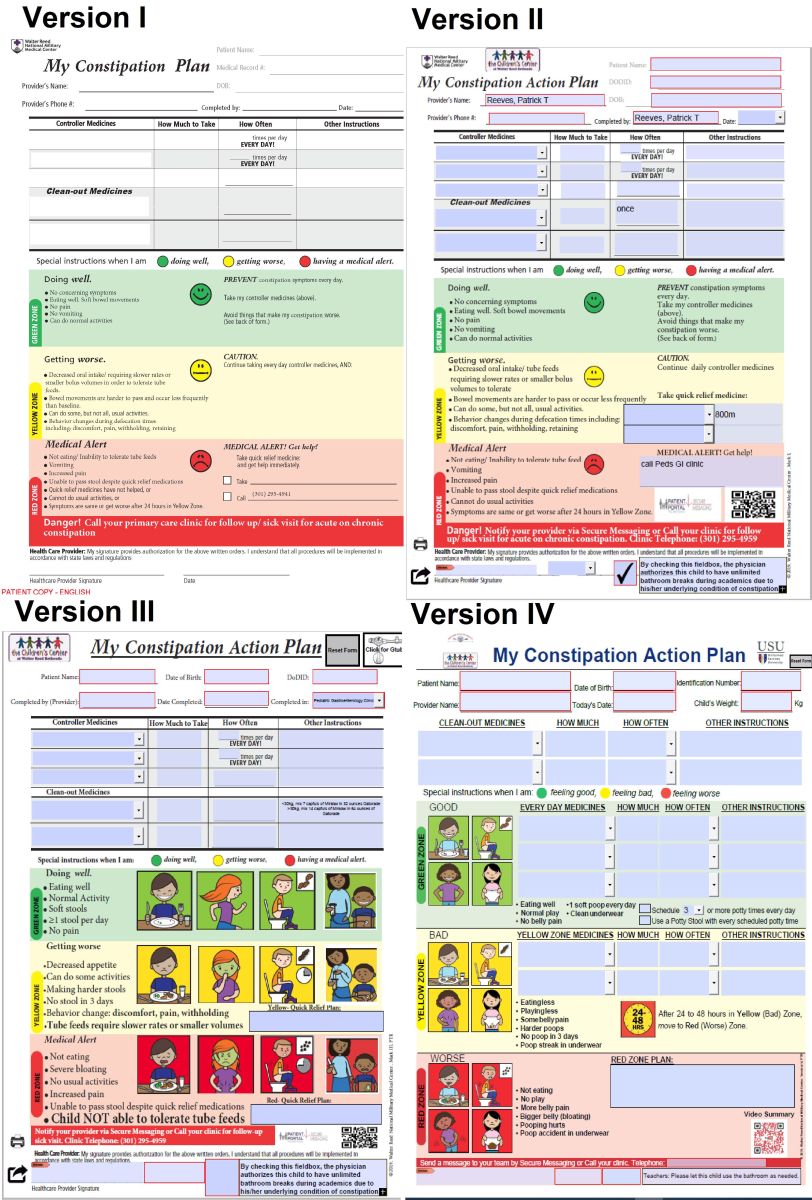

Reeves PT, Kolasinski NT, Yin HS et al (2021) Development and assessment of a pictographic pediatric constipation action plan. J Pediatr. 229:118-126.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.10.001

Reeves PT, Meyers TP, Howard B et al (2025) Potty stools, a pilot study to step up the management of functional constipation in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 64(4):558-563. https://doi.org/10.1177/00099228241278900

Rego RMP, Machado NC, Carvalho MA et al (2024) Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation: an adjuvant treatment for intractable constipation in children. Biomedicines. 12(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010164

Sadeghvand S, Taghizadeh Orangi A, Mansouripour S et al (2025) Constipation in children with cerebral palsy: prevalence, clinical manifestations, and polyethylene glycol vs. lactulose efficacy. Iran J Child Neurol. 19(3):71-76. https://doi.org/10.22037/ijcn.v19i3.45043

Seidenfaden S, Ormarsson OT, Lund SH et al (2018) Physical activity may decrease the likelihood of children developing constipation. Acta Paediatr. 107:151-155. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14067

Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY et al (2014) Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 58(2):258–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000266

Tappin D, Grzeda M, Joinson C et al (2020) Challenging the view that lack of fibre causes childhood constipation. Arch Dis Child. 105:864–868. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-318082

The Children’s Mercy Hospital (2022) Unstuck: your family’s guide to childhood constipation. https://www.childrensmercy.org/siteassets/media-documents-for-depts-section/departments/gastroenterology/getting-unstuck.pdf (accessed 20 November 2025)

Wang L, Xu M, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Li Y (2020) The effectiveness of acupuncture in management of functional constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020:6137450. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6137450

Yang WC, Zeng BS, Liang CS et al (2024) Efficacy and acceptability of different probiotic products plus laxatives for pediatric functional constipation: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pediatr. 183(8):3531-3541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05568-6

Al-Beltagi M, Saeed NK, Bediwy AS (2025) Exploring the gut-exercise link: A systematic review of gastrointestinal disorders in physical activity. World J Gastroenterol. 31(22): 106835. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i22.106835

Bashir SK, Khan MB (2024) Pediatric functional constipation: a new challenge. Advanced Gut Microbiome Research. 2024(1):5569563. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/5569563

Chase J, Shields N (2011) A systematic review of the efficacy of non-pharmacological, non-surgical and non-behavioural treatments of functional chronic constipation in children. The Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal. 17(2):40-50

Chen K, Zhou Z, Nie S et al (2024) Adjunctive efficacy of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis XLTG11 for functional constipation in children. Braz J Microbiol. 55(2):1317-1330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-024-01276-3

de Geus A, Koppen LJN, Flin RB et al (2023) An update of pharmacological management in children with functional constipation. Pediatric Drugs. 25:343–358 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-023-00563-0

Dierkes J, Nwaru BI, Ramel A et al (2023) Dietary fiber and growth, iron status and bowel function in children 0-5 years old: a systematic review. Food Nutr Res. 67. https://doi.org/10.29219/fnr.v67.9011

Doğan İG, Gürşen C, Akbayrak T et al (2022) Abdominal massage in functional chronic constipation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phys Ther. 102:pzac058. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac058

Ellis MR, Meadows S (2002) Clinical inquiries. What is the best therapy for constipation in infants? J Fam Pract. 51(8):682

Erdogan A, Rao S, Thiruvaiyaru D et al (2016) Randomized clinical trial: soluble/insoluble fiber or psyllium for chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 44(1):35–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13647

Gearry R, Fukudo S, Barbara G et al (2023) Consumption of 2 green kiwifruits daily improves constipation and abdominal comfort—results of an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 118:1058–1068. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002124

Hozyasz K (2023) Dietetic treatment of functional constipation in children: a scoping review with narrative summary [Polish]. Long-Term Care Nursing. 8(1):34-55. https://doi.org/10.19251/pwod/2023.1(4)

Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M (2016) Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology. 150(6):1456–1468.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.015

Iacona R, Ramage L, Malakounides G (2019) Current state of neuromodulation for constipation and fecal incontinence in children: a systematic review. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 29(6):495-503. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1677485

Jarzebicka D, Sieczkowska J, Dadalski M, Kierkus J, Ryzko J, Oracz G (2016) Evaluation of the effectiveness of biofeedback therapy for functional constipation in children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 27(5):433-438. https://doi.org/10.5152/tjg.2016.16140

Koyama T, Nagata N, Nishiura K, Miura N, Kawai T, Yamamoto H (2022) Prune juice containing sorbitol, pectin, and polyphenol ameliorates subjective complaints and hard feces while normalizing stool in chronic constipation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 117(10):1714-1717. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001931

Lee-Robichaud H, Thomas K, Morgan J et al (2010) lactulose versus polyethylene glycol for chronic constipation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (7):CD007570. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007570.pub2

Leung AKC, Hon KL (2021) Paediatrics: how to manage functional constipation. Drugs in Context. 10: 2020-11-2. https://doi.org/10.7573/dic.2020-11-2

Levy EI, Lemmens R, Vandenplas Y, Devreker T (2017) Functional constipation in children: challenges and solutions. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 8:19-27. https://doi.org/10.2147/PHMT.S110940

Liu Z, Gang L, Yunwei M, Lin L (2021) Clinical efficacy of infantile massage in the treatment of infant functional constipation: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 9:663581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.663581

Malekiantaghi A, Miladi M, Ostadan MT et al (2025) Abdominal massage as an adjunctive therapy for pediatric functional constipation: a randomized controlled trial. Turk J Pediatr. 67(5):669-677. https://doi.org/10.24953/turkjpediatr.2025.6367

Mulhem E, Khondoker F, Kandiah S (2022) Constipation in children and adolescents: evaluation and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 105(5):469-478

Narula Khanna H, Roy S, Shaikh A et al (2025) Impact of probiotic supplements on behavioural and gastrointestinal symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr Open. 9(1):e003045. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2024-003045

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. CG99. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99/chapter/Recommendations#clinical-management (accessed 6 November 2025)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2025) Constipation in children: choice of laxatives. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/constipation-in-children/prescribing-information/choice-of-laxatives/ (accessed 13 November 2025)

Reeves PT, Kolasinski NT, Yin HS et al (2021) Development and assessment of a pictographic pediatric constipation action plan. J Pediatr. 229:118-126.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.10.001

Reeves PT, Meyers TP, Howard B et al (2025) Potty stools, a pilot study to step up the management of functional constipation in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 64(4):558-563. https://doi.org/10.1177/00099228241278900

Rego RMP, Machado NC, Carvalho MA et al (2024) Transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation: an adjuvant treatment for intractable constipation in children. Biomedicines. 12(1):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010164

Sadeghvand S, Taghizadeh Orangi A, Mansouripour S et al (2025) Constipation in children with cerebral palsy: prevalence, clinical manifestations, and polyethylene glycol vs. lactulose efficacy. Iran J Child Neurol. 19(3):71-76. https://doi.org/10.22037/ijcn.v19i3.45043

Seidenfaden S, Ormarsson OT, Lund SH et al (2018) Physical activity may decrease the likelihood of children developing constipation. Acta Paediatr. 107:151-155. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14067

Tabbers MM, DiLorenzo C, Berger MY et al (2014) Evaluation and treatment of functional constipation in infants and children: evidence-based recommendations from ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 58(2):258–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000000266

Tappin D, Grzeda M, Joinson C et al (2020) Challenging the view that lack of fibre causes childhood constipation. Arch Dis Child. 105:864–868. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2019-318082

The Children’s Mercy Hospital (2022) Unstuck: your family’s guide to childhood constipation. https://www.childrensmercy.org/siteassets/media-documents-for-depts-section/departments/gastroenterology/getting-unstuck.pdf (accessed 20 November 2025)

Wang L, Xu M, Zheng Q, Zhang W, Li Y (2020) The effectiveness of acupuncture in management of functional constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020:6137450. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6137450

Yang WC, Zeng BS, Liang CS et al (2024) Efficacy and acceptability of different probiotic products plus laxatives for pediatric functional constipation: a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pediatr. 183(8):3531-3541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05568-6

.jpg)

Figure 3. Encouraging sorbitol-rich fruits (such as dried fruits) in a child's diet helps to keep the stool soft.

Figure 3. Encouraging sorbitol-rich fruits (such as dried fruits) in a child's diet helps to keep the stool soft.